Bézier curve

A Bézier curve is a parametric curve frequently used in computer graphics and related fields. Generalizations of Bézier curves to higher dimensions are called Bézier surfaces, of which the Bézier triangle is a special case.

In vector graphics, Bézier curves are used to model smooth curves that can be scaled indefinitely. "Paths," as they are commonly referred to in image manipulation programs,[note 1] are combinations of linked Bézier curves. Paths are not bound by the limits of rasterized images and are intuitive to modify. Bézier curves are also used in animation as a tool to control motion.[note 2]

Bézier curves are also used in the time domain, particularly in animation and interface design, e.g., a Bézier curve can be used to specify the velocity over time of an object such as an icon moving from A to B, rather than simply moving at a fixed number of pixels per step. When animators or interface designers talk about the "physics" or "feel" of an operation, they may be referring to the particular Bézier curve used to control the velocity over time of the move in question.

Bézier curves were widely publicized in 1962 by the French engineer Pierre Bézier, who used them to design automobile bodies. The curves were first developed in 1959 by Paul de Casteljau using de Casteljau's algorithm, a numerically stable method to evaluate Bézier curves.

Contents |

Applications

Computer graphics

Bézier curves are widely used in computer graphics to model smooth curves. As the curve is completely contained in the convex hull of its control points, the points can be graphically displayed and used to manipulate the curve intuitively. Affine transformations such as translation, and rotation can be applied on the curve by applying the respective transform on the control points of the curve.

Quadratic and cubic Bézier curves are most common; higher degree curves are more expensive to evaluate. When more complex shapes are needed, low order Bézier curves are patched together. This is commonly referred to as a "path" in vector graphics standards (like SVG) and vector graphics programs (like Adobe Illustrator and Inkscape). To guarantee smoothness, the control point at which two curves meet must be on the line between the two control points on either side.

The simplest method for scan converting (rasterizing) a Bézier curve is to evaluate it at many closely spaced points and scan convert the approximating sequence of line segments. However, this does not guarantee that the rasterized output looks sufficiently smooth, because the points may be spaced too far apart. Conversely it may generate too many points in areas where the curve is close to linear. A common adaptive method is recursive subdivision, in which a curve's control points are checked to see if the curve approximates a line segment to within a small tolerance. If not, the curve is subdivided parametrically into two segments, 0 ≤ t ≤ 0.5 and 0.5 ≤ t ≤ 1, and the same procedure is applied recursively to each half. There are also forward differencing methods, but great care must be taken to analyse error propagation. Analytical methods where a spline is intersected with each scan line involve finding roots of cubic polynomials (for cubic splines) and dealing with multiple roots, so they are not often used in practice.

Animation

In animation applications, such as Adobe Flash and Synfig, Bézier curves are used to outline, for example, movement. Users outline the wanted path in Bézier curves, and the application creates the needed frames for the object to move along the path. For 3D animation Bézier curves are often used to define 3D paths as well as 2D curves for keyframe interpolation.

Fonts

TrueType fonts use Bézier splines composed of quadratic Bézier curves. Modern imaging systems like PostScript, Asymptote, Metafont, and SVG use Bézier splines composed of cubic Bézier curves for drawing curved shapes. OpenType fonts can use either types, depending on the flavor of the font.

The internal rendering of all Bézier curves in font or vector graphics renderers will split them recursively up to the point where the curve is flat enough to be drawn as a series of linear or circular segments. The exact splitting algorithm is implementation dependent, only the flatness criteria must be respected to reach the necessary precision and to avoid non-monotonic local changes of curvature. The "smooth curve" feature of charts in Microsoft Excel also use this algorithm.[1]

Because arcs of circles and ellipses cannot be exactly represented by Bézier curves, they are first approximated by Bézier curves, which are in turn approximated by arcs of circles. This is inefficient as there exists also approximations of all Bézier curves using arcs of circles or ellipses, which can be rendered incrementally with arbitrary precision. Another approach, used by modern hardware graphics adapters with accelerated geometry, can convert exactly all Bézier and conic curves (or surfaces) into NURBS, that can be rendered incrementally without first splitting the curve recursively to reach the necessary flatness condition. This approach also allows preserving the curve definition under all linear or perspective 2D and 3D transforms and projections.

Font engines, like FreeType, draw the font's curves (and lines) on a pixellated surface, in a process called Font rasterization.[2]

Examination of cases

A Bézier curve is defined by a set of control points P0 through Pn, where n is called its order (n = 1 for linear, 2 for quadratic, etc.). The first and last control points are always the end points of the curve; however, the intermediate control points (if any) generally do not lie on the curve.

Linear Bézier curves

Given points P0 and P1, a linear Bézier curve is simply a straight line between those two points. The curve is given by

and is equivalent to linear interpolation.

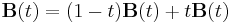

Quadratic Bézier curves

A quadratic Bézier curve is the path traced by the function B(t), given points P0, P1, and P2,

![\mathbf{B}(t) = (1 - t)[(1 - t) \mathbf P_0 %2B t \mathbf P_1] %2B t [(1 - t) \mathbf P_1 %2B t \mathbf P_2] \mbox{ , } t \in [0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/09d743f944f43b8c8a3c8468cabdb072.png) ,

,

which can be interpreted as the linear interpolant of corresponding points on the linear Bézier curves from P0 to P1 and from P1 to P2 respectively. More explicitly it can be written as:

It departs from P0 in the direction of P1, then bends to arrive at P2 in the direction from P1. In other words, the tangents in P0 and P2 both pass through P1. This is directly seen from the derivative of the Bézier curve:

A quadratic Bézier curve is also a parabolic segment. As a parabola is a conic section, some sources refer to quadratic Béziers as "conic arcs".[2]

Cubic Bézier curves

Four points P0, P1, P2 and P3 in the plane or in higher-dimensional space define a cubic Bézier curve. The curve starts at P0 going toward P1 and arrives at P3 coming from the direction of P2. Usually, it will not pass through P1 or P2; these points are only there to provide directional information. The distance between P0 and P1 determines "how long" the curve moves into direction P2 before turning towards P3.

Writing BPi,Pj,Pk(t) for the quadratic Bézier curve defined by points Pi, Pj, and Pk, the cubic Bézier curve can be defined as a linear combination of two quadratic Bézier curves:

The explicit form of the curve is:

For some choices of P1 and P2 the curve may intersect itself, or contain a cusp.

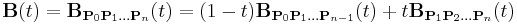

Generalization

Bézier curves can be defined for any degree n.

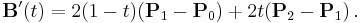

Recursive definition

A recursive definition for the Bézier curve of degree n expresses it as a linear interpolation between two Bézier curves of degree n − 1.

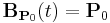

Let  denote the Bézier curve determined by the points P0, P1, ..., Pn. Then

denote the Bézier curve determined by the points P0, P1, ..., Pn. Then

to start, and

to start, and

This recursion is elucidated in the animations below.

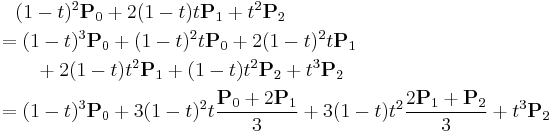

Explicit definition

The formula can be expressed explicitly as follows:

where  is the binomial coefficient.

is the binomial coefficient.

For example, for n = 5:

Terminology

Some terminology is associated with these parametric curves. We have

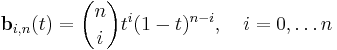

where the polynomials

are known as Bernstein basis polynomials of degree n, defining t0 = 1 and (1 − t)0 = 1. The binomial coefficient,  , has the alternative notation,

, has the alternative notation,

The points Pi are called control points for the Bézier curve. The polygon formed by connecting the Bézier points with lines, starting with P0 and finishing with Pn, is called the Bézier polygon (or control polygon). The convex hull of the Bézier polygon contains the Bézier curve.

Properties

- The curve begins at P0 and ends at Pn; this is the so-called endpoint interpolation property.

- The curve is a straight line if and only if all the control points are collinear.

- The start (end) of the curve is tangent to the first (last) section of the Bézier polygon.

- A curve can be split at any point into two subcurves, or into arbitrarily many subcurves, each of which is also a Bézier curve.

- Some curves that seem simple, such as the circle, cannot be described exactly by a Bézier or piecewise Bézier curve; though a four-piece cubic Bézier curve can approximate a circle (see Bézier spline), with a maximum radial error of less than one part in a thousand, when each inner control point (or offline point) is the distance

horizontally or vertically from an outer control point on a unit circle. More generally, an n-piece cubic Bézier curve can approximate a circle, when each inner control point is the distance

horizontally or vertically from an outer control point on a unit circle. More generally, an n-piece cubic Bézier curve can approximate a circle, when each inner control point is the distance  from an outer control point on a unit circle, where t is 360/n degrees, and n > 2.

from an outer control point on a unit circle, where t is 360/n degrees, and n > 2. - The curve at a fixed offset from a given Bézier curve, often called an offset curve (lying "parallel" to the original curve, like the offset between rails in a railroad track), cannot be exactly formed by a Bézier curve (except in some trivial cases). However, there are heuristic methods that usually give an adequate approximation for practical purposes.

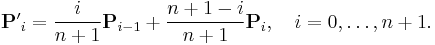

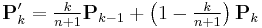

- Every quadratic Bézier curve is also a cubic Bézier curve, and more generally, every degree n Bézier curve is also a degree m curve for any m > n. In detail, a degree n curve with control points P0, …, Pn is equivalent (including the parametrization) to the degree n + 1 curve with control points P'0, …, P'n + 1, where

.

.

Constructing Bézier curves

Linear curves

| Animation of a linear Bézier curve, t in [0,1] |

The t in the function for a linear Bézier curve can be thought of as describing how far B(t) is from P0 to P1. For example when t=0.25, B(t) is one quarter of the way from point P0 to P1. As t varies from 0 to 1, B(t) describes a straight line from P0 to P1.

Quadratic curves

For quadratic Bézier curves one can construct intermediate points Q0 and Q1 such that as t varies from 0 to 1:

- Point Q0 varies from P0 to P1 and describes a linear Bézier curve.

- Point Q1 varies from P1 to P2 and describes a linear Bézier curve.

- Point B(t) varies from Q0 to Q1 and describes a quadratic Bézier curve.

| Construction of a quadratic Bézier curve | Animation of a quadratic Bézier curve, t in [0,1] |

Higher-order curves

For higher-order curves one needs correspondingly more intermediate points. For cubic curves one can construct intermediate points Q0, Q1, and Q2 that describe linear Bézier curves, and points R0 & R1 that describe quadratic Bézier curves:

| Construction of a cubic Bézier curve | Animation of a cubic Bézier curve, t in [0,1] |

For fourth-order curves one can construct intermediate points Q0, Q1, Q2 & Q3 that describe linear Bézier curves, points R0, R1 & R2 that describe quadratic Bézier curves, and points S0 & S1 that describe cubic Bézier curves:

| Construction of a quartic Bézier curve | Animation of a quartic Bézier curve, t in [0,1] |

For fifth-order curves, one can construct similar intermediate points.

| Animation of a fifth order Bézier curve, t in [0,1] |

Degree elevation

A Bézier curve of degree n can be converted into a Bézier curve of degree n + 1 with the same shape. This is useful if software supports Bézier curves only of specific degree. For example, you can draw a quadratic Bézier curve with Cairo, which supports only cubic Bézier curves.

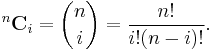

To do degree elevation, we use the equality  . Each component

. Each component  is multiplied by (1 − t) or t, thus increasing a degree by one. Here is the example of increasing degree from 2 to 3.

is multiplied by (1 − t) or t, thus increasing a degree by one. Here is the example of increasing degree from 2 to 3.

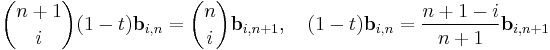

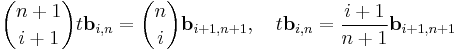

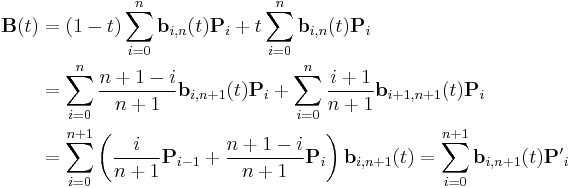

For arbitrary n we use equalities

introducing arbitrary  and

and  .

.

Therefore new control points are [3]

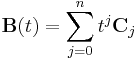

Polynomial form

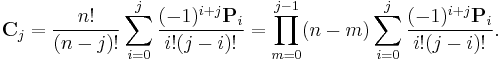

Sometimes it is desirable to express the Bézier curve as a polynomial instead of a sum of less straightforward Bernstein polynomials. Application of the binomial theorem to the definition of the curve followed by some rearrangement will yield:

where

This could be practical if  can be computed prior to many evaluations of

can be computed prior to many evaluations of  ; however one should use caution as high order curves may lack numeric stability (de Casteljau's algorithm should be used if this occurs). Note that the empty product is 1.

; however one should use caution as high order curves may lack numeric stability (de Casteljau's algorithm should be used if this occurs). Note that the empty product is 1.

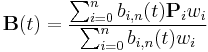

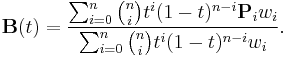

Rational Bézier curves

The rational Bézier curve adds adjustable weights to provide closer approximations to arbitrary shapes. The numerator is a weighted Bernstein-form Bézier curve and the denominator is a weighted sum of Bernstein polynomials. Rational Bézier curves can, among other uses, be used to represent segments of conic sections exactly.[4]

Given n + 1 control points Pi, the rational Bézier curve can be described by:

or simply

See also

- NURBS

- String art – Bézier curves are also formed by many common forms of string art, where strings are looped across a frame of nails.

- Hermite curve

Notes

- ^ Image manipulation programs such as Inkscape, Adobe Photoshop, and GIMP.

- ^ In animation applications such as Adobe Flash, Adobe After Effects, Microsoft Expression Blend, Blender, Autodesk Maya and Autodesk 3ds max.

References

- ^ http://www.xlrotor.com/resources/files.shtml

- ^ a b FreeType Glyph Conventions, David Turner + Freetype Development Team, Freetype.org, retr May 2011

- ^ Farin, Gerald (1997), Curves and surfaces for computer-aided geometric design (4 ed.), Elsevier Science & Technology Books, ISBN 978 0 12249054 5

- ^ Neil Dodgson (2000-09-25). "Some Mathematical Elements of Graphics: Rational B-splines". http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/2000/AGraphHCI/SMEG/node5.html. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- Paul Bourke: Bézier Surfaces (in 3D), http://local.wasp.uwa.edu.au/~pbourke/geometry/bezier/index.html

- Donald Knuth: Metafont: the Program, Addison-Wesley 1986, pp. 123–131. Excellent discussion of implementation details; available for free as part of the TeX distribution.

- Dr Thomas Sederberg, BYU Bézier curves, http://www.tsplines.com/resources/class_notes/Bezier_curves.pdf

- J.D. Foley et al.: Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice in C (2nd ed., Addison Wesley, 1992)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Bézier Curve" from MathWorld.

- Finding All Intersections of Two Bézier Curves. – Locating all the intersections between two Bézier curves is a difficult general problem, because of the variety of degenerate cases. By Richard J. Kinch.

- From Bézier to Bernstein Feature Column from American Mathematical Society

- A Primer on Bézier Curves A detailed explanation of implementing Bezier curves and associated graphics algorithms, with interactive graphics

![\mathbf{B}(t)=\mathbf{P}_0 %2B t(\mathbf{P}_1-\mathbf{P}_0)=(1-t)\mathbf{P}_0 %2B t\mathbf{P}_1 \mbox{ , } t \in [0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ad90a6fecd5324dc32f75f0b19c2d684.png)

![\mathbf{B}(t) = (1 - t)^{2}\mathbf{P}_0 %2B 2(1 - t)t\mathbf{P}_1 %2B t^{2}\mathbf{P}_2 \mbox{ , } t \in [0,1].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2d5e5d58562d8ec2c35f16df98d2b974.png)

![\mathbf{B}(t)=(1-t)\mathbf{B}_{\mathbf P_0,\mathbf P_1,\mathbf P_2}(t) %2B t \mathbf{B}_{\mathbf P_1,\mathbf P_2,\mathbf P_3}(t) \mbox{ , } t \in [0,1].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fdbeda5f0c7bbea16e80663c606ba863.png)

![\mathbf{B}(t)=(1-t)^3\mathbf{P}_0%2B3(1-t)^2t\mathbf{P}_1%2B3(1-t)t^2\mathbf{P}_2%2Bt^3\mathbf{P}_3 \mbox{ , } t \in [0,1].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5e32b674a98a9f70e492851f9ad92b61.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathbf{B}(t) & = \sum_{i=0}^n {n\choose i}(1-t)^{n-i}t^i\mathbf{P}_i \\

& = (1-t)^n\mathbf{P}_0 %2B {n\choose 1}(1-t)^{n-1}t\mathbf{P}_1 %2B \cdots \\

& {} \quad \cdots %2B {n\choose n-1}(1-t)t^{n-1}\mathbf{P}_{n-1} %2B t^n\mathbf{P}_n,\quad t \in [0,1],

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bdee8563f3166da2f37c1e812cc8aa60.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathbf{B}(t) & = (1-t)^5\mathbf{P}_0 %2B 5t(1-t)^4\mathbf{P}_1 %2B 10t^2(1-t)^3 \mathbf{P}_2 \\

& {} \quad %2B 10t^3 (1-t)^2 \mathbf{P}_3 %2B 5t^4(1-t) \mathbf{P}_4 %2B t^5 \mathbf{P}_5,\quad t \in [0,1].

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3b5416b82078d1c1ef33382d3cd28e8e.png)

![\mathbf{B}(t) = \sum_{i=0}^n \mathbf{b}_{i,n}(t)\mathbf{P}_i,\quad t\in[0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f03e0da823da62ab676bd8291d280b7a.png)